How collaboration paved the way for a stronger crisis system in Tulsa

Tulsa has spent years developing resources to meet people in a behavioral health crisis with the right response at the right time.

Today, the city has a robust crisis system, with dedicated crisis call lines, innovative mobile teams that pair mental health professionals with police or paramedics, and crisis units that operate like urgent care clinics for short-term stabilization.

But data showed a missing piece: Tulsa’s 911 center still received thousands of mental health-related calls annually — calls that could often be better handled by mental health professionals.

With Healthy Minds' guidance, Tulsa’s First Responders Advisory Council set out last year to find a solution.

The council, a working group that unites public safety and mental health providers, wanted not only to ensure people who call 911 in a mental health crisis get the best possible response, but also to save time and money for first responders.

“It became increasingly clear that it would be beneficial to a lot of people to have a diversion system,” said Audra Brulc, who facilitates the group as part of her role as a community initiatives manager at Healthy Minds Policy Initiative.

To that end, Family and Children’s Services, a Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic in Tulsa, worked with the city to embed its clinicians around the clock at the 911 center, adopting a successful practice seen in other large cities.

These professionals now work 24/7 to handle mental health-related 911 calls for the entire city — not just Family and Children’s clients.

“Our ideal outcome was to provide callers who might be experiencing a mental health crisis with an immediate resource that would address the situation,” said John Mulligan, clinical supervisor for COPES, the crisis hotline and mobile response service operated by Family and Children’s Services.

Now, embedded COPES clinicians can also send out civilian mental health response teams — staffed only by mental health professionals — in response to 911 calls, Mulligan said.

Since launching 24/7 in February, the program has drastically cut down on the number of mental health calls that require a police or fire department response.

In doing so, the program also keeps people out of emergency rooms and jails when they can be better served with mental health resources in the community.

Dedicated mental health lines like 988 or the COPES crisis line are the ideal way for Oklahomans to get help in a mental health crisis. Call-takers are trained mental health professionals who can often get a caller the help they need over the phone, and they can send out mobile teams to offer more help in the field when necessary.

But now, with mental health clinicians working at the 911 center, there is no “wrong door” for Tulsans in a mental health crisis.

‘It’s better for the public’

Working on patrol when the call diversion program launched, Lt. Naresh Persaud felt the difference right away.

“All of a sudden, we were not getting the same amount of mental health crisis calls,” said Persaud, now supervisor over the Tulsa Police Department’s mental health unit.

Tulsa police do receive significant training on responding to mental health calls — and still, they’re generally not the best equipped responders in a mental health crisis, Persaud said.

Since the call diversion program at Tulsa’s 911 center launched, mental health clinicians have diverted over 3,200 calls away from first responders.

For Tulsa Police, that means officers have more time to respond to calls critical to public safety. To date, the program has saved well over 1,800 hours and about $94,500 for the police department.

The benefit is multi-fold: embedded clinicians can spend the extra time over the phone with someone who called 911 for mental health help. And because the calls are often handled solely over the phone, that means police cars, fire trucks, and ambulances can stay in service, ready to respond to public safety emergencies faster.

“It's better for the public, it's better for officer safety, and it's better for the citizens that are calling in mental health crisis,” Persaud said.

'Exponential growth’ in Tulsa’s crisis system

The call diversion program is part of Tulsa’s “exponential growth” in capability and efficiency of the city’s crisis system, said Justin Lemery, chief of emergency medical services and mobile integrated healthcare at the Tulsa Fire Department.

A few years ago, if a Tulsa resident called in a mental health crisis, they were likely to receive a traditional response from police, firefighters, or an ambulance service, Lemery said. First responders would show up and do their best to mitigate the crisis, but a lot of times people would wind up in emergency rooms, which are often ill-equipped to help people in a behavioral health crisis. Sometimes, people would end up in jail.

“There were a lot of inefficiencies with that response, and that’s not the case today,” Lemery said. “Now, not only do you get the right responders on the scene, but over 80% of the time, you are getting that individual taken care of over the phone. You didn’t see that a couple of years ago.”

Tulsa’s progress in strengthening and streamlining its crisis system is the product of years of collaboration between first responders and behavioral health providers — most recently through Tulsa’s First Responders Advisory Council, which reconvened in 2023 with Healthy Minds’ facilitation.

“Healthy Minds has been catalytic in their approach to doing this and bringing people to the table to have conversations,” Lemery said. “It’s not always easy work, and there have to be tough conversations. When you have these groups like the First Responders Advisory Council, you can have some of those tough conversations that help move the ball forward.”

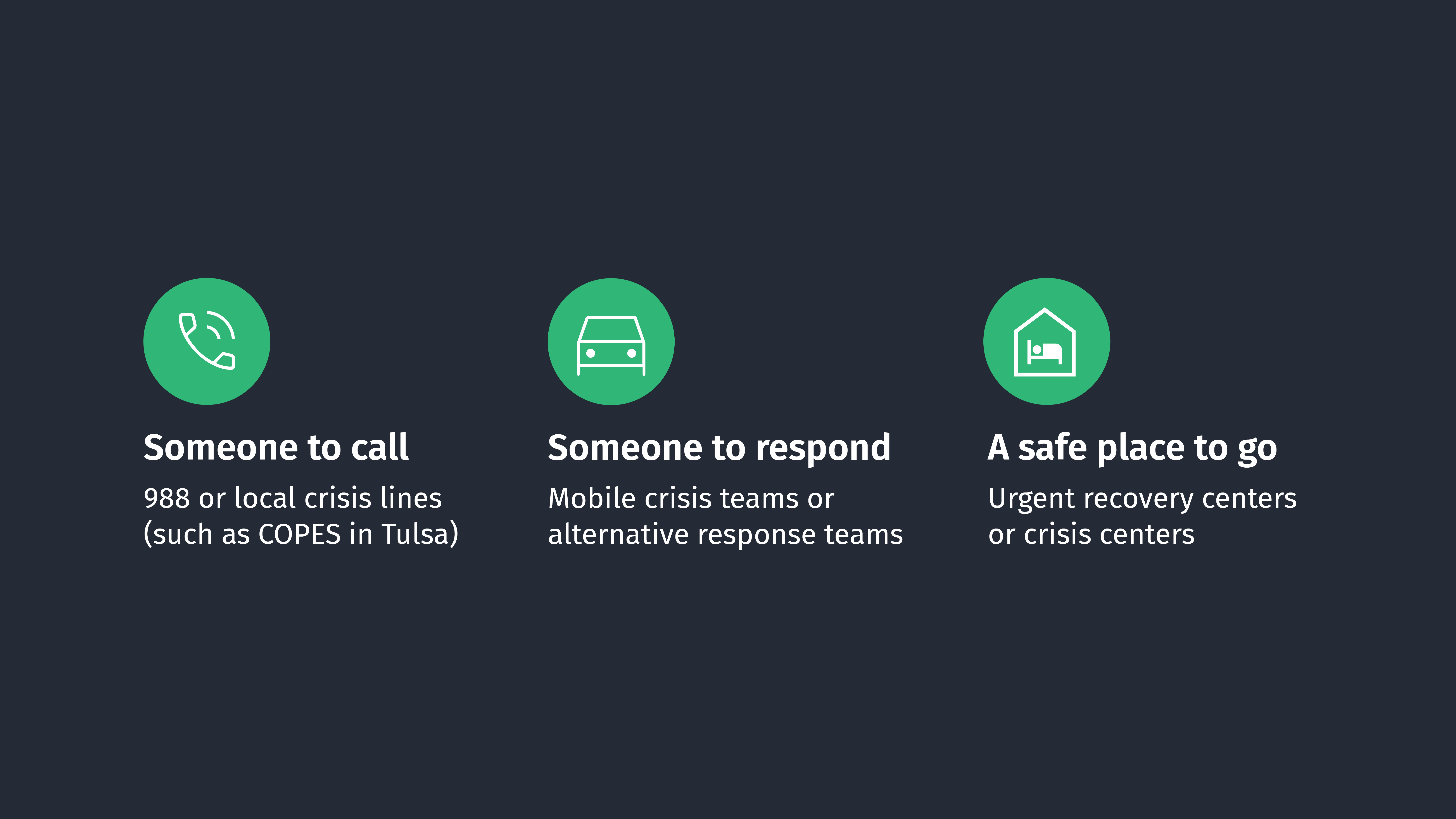

As operators of Tulsa’s crisis system, the group identifies and solves pain points across the crisis system, aimed at ensuring Tulsans have someone to call, someone to respond, and a safe place to go in a mental health crisis.

Tulsa’s leaders have long been committed to this kind of work. Before the group formally reconvened, community leaders saw a need for greater capacity at Tulsa’s CrisisCare Center — and the need for police to be able to quickly and safely drop residents off there when appropriate.

With Healthy Minds’ help to secure additional state funding, the CrisisCare Center increased its capacity by 30% and added a dedicated entrance for law enforcement, making it much quicker and easier for first responders to get people to the right place for care.

With these partnerships — and by leveraging Tulsa’s other crisis facilities at GRAND Mental Health and Counseling and Recovery Services — Tulsa has positioned itself as a national leader in how a community can work collaboratively respond to mental health crises, said Zack Stoycoff, Healthy Minds’ executive director.

“The way Tulsa’s crisis system works today is better than it ever has,” he said. “These initiatives are now indispensable to the city, and we need to make sure they continue for a long time.”